On Monday, we reached the northernmost point of the cruise track and we were in thick ice. This meant that it was time to get off the boat and do an ice station. The ship pulled into the ice and “parked†in order for the scientists to disembark and begin a sampling station on top of the Bering Sea ice.Â

Before heading out onto the ice, the Captain held a briefing to tell us the procedure for sampling in the ice. We had to wear special dry suits, Mustang MSD900s in case we fell in. These proved to be challenging to put on but very warm and relatively comfortable for our day on the ice. Other than that, he told us that a rescue swimmer would be out on the ice, a polar bear watch person would be on the ship and another would be on the ice with a rifle in case a polar bear charged. We are generally too far south to see polar bears but they need to follow procedure. Of course, the bear would not be shot as this is only a precaution. If a bear was spotted, we would have to hurry off the ice and let the bear pass through.Â

After suiting up, we heading down the brow and out onto the ice with all of the gear. There were a few different research teams heading out to sample and we all found our sampling spots and began work. I was helping Dr. Ned Cokelet and the team from NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle. The team is looking at the physical and chemical properties of ice in order to determine how these parameters affect the organisms that live in the ice (phytoplankton, ice algae and other microscopic critters live in the ice).Â

We set to work to find a good sampling spot and did a preliminary core to check on the thickness of the ice. It was about 30cm thick and it looked like they picked a good spot. The team set out to take two cores with a specialized auger and drill out a series of brine holes to different depths. The two cores are cut into 10cm segments which will be tested for temperature while out on the ice and then salinity, chlorophyll and other nutrients back on board the ship. In this way, the team can get temperature profiles of the ice and profiles of the nutrient and chlorophyll distribution of the ice. The ice is not solid but has brine pockets throughout with varying salinities and levels of nutrients and chlorophyll. The brine wells are dug to various depths and the water that fills them will be tested for salinity, nutrients and chlorophyll as well. This will tell the team what is happening in the ice from a physical standpoint.Â

Dylan Righi supervises Gaelin Rosenwaks taking a core in front of the USCGC Healy. This core will be analyzed for the ice algae growing on the bottom. Â

Rolf Sonnerup and David Strausz carefully pack and label samples from an ice core. Â

The samples and information from the PMEL group are important segments in understanding how the sea ice affects the overall ecosystem as it fits into the broader questions of the Bering Sea Ecosystem Project.Â

David Strausz, Dylan Righi and Ned Cokelet measure the depth of one of their brine wells before sampling the brine for salinity and other nutrients. Â

After the sampling was completed, we had time to explore the ice and enjoy a little sunshine while atop the Bering Sea! It was amazing to be walking on top of one of the roughest bodies of water in the world. Not only that but it was sunny and warm (well for up here). The rest of the crew was also allowed off the ship and everyone enjoyed an afternoon on the ice playing kickball and just relaxing on what felt like something solid even though we were floating on top of the sea. Viewing the ship from below on the ice made quite an impression and it was interesting to get another vantage point.Â

The crew enjoys some time off the ship after the science sampling was completed.

I tried to move the ship. It was too big.Â

A beautiful sunset capped off a beautiful (rare) “sunshiney†day in the Bering Sea.

Â

Â

The sediment trap buoys adrift in the Bering Sea

The sediment trap buoys adrift in the Bering Sea

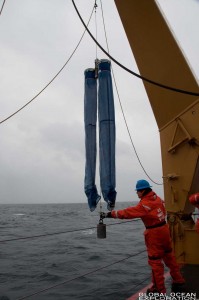

Over the pipes, an announcement to get the small boats ready for launch came over in the early afternoon. It was time to retrieve the sediment traps that had been deployed the previous afternoon. Floating and drifting in the Bering Sea for 24 hours while the ship went about its other business, the sediment trap’s beacon had emailed the researchers, Roger Kelly from the University of Rhode Island and Jonathan Whitfield from the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, the current location of the instrument. The bridge had the bright orange buoy in sight and Roger Kelly was in the boat with the Coast Guard crew ready to retrieve it. This is easier said than done.

Deployment is simple enough as the collection tubes are set up and lowered into the sea after which the bright orange buoys are attached and lowered followed by the buoy that resembles a lobster buoy with a light on top and the satellite beacon. After the instrument is carefully deployed, it drifts about in the sea for 24 hours collecting sediment that falls from the surface. The traps are deployed in deep water (over 300 meters) and usually on the shelf break where there is a high degree of productivity.Â

The small boat making contact with the instrument and towing it towards the ship.  Roger Kelly tends the buoy line.

Retrieval is more complicated. The small boats are launched into the rough waters of the Bering Sea where the crew must reach the trap and tow it closer to the ship where the winches can be used to bring the samples up carefully. Once the buoy is reached and towed, a line is thrown from the ship and secured to the trap, which is then carefully brought in. The great skill of the small boat operators and marine science technicians with the direction of the scientists makes the process go smoothly (most of the time).Â

The instrument is about to come aboard as the small boat grabs a tender line from the ship.Â

The instrument is about to come aboard as the small boat grabs a tender line from the ship.Â

The tubes with the samples are carefully collected by Jonathan Whitfield and MST Tiffany Wright for analysis.

The tubes with the samples are carefully collected by Jonathan Whitfield and MST Tiffany Wright for analysis.

On the most recent deployment, I was out on deck for the retrieval of the samples. When the first sample came up, it was filled with copepods and other critters. This was the surface sample where we would expect the animals to reside. The sediment sample collects in the bottom of the tube. This sample is then filtered and processed both on board and back at their lab to determine the amount of organic carbon in the water column. Once processed, the scientists are able to determine which organisms are contributing to the material which is made up primarily of animal waste and dead matter.Â

The surface collection tubes sometimes capture animals from the water column.  In this tube, there are copepods and a ctenophore (comb jelly) amongst other small critters.

The surface collection tubes sometimes capture animals from the water column.  In this tube, there are copepods and a ctenophore (comb jelly) amongst other small critters.

With the information learned from the sediment trap samples, the scientists are trying to put together pieces of the carbon cycle in order to find the flux of particulate organic carbon from the surface water into deep waters. Upper waters will draw down carbon dioxide into the water and convert it to organic carbon via photosynthesis. This carbon will then sink to the sea floor and could in turn draw down more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere which would be good for some of our problems but may cause harm to marine organisms. This project is seeking to find a baseline of what is happening in the system now so that in the future we will be able to measure the changes in carbon export in our changing world.Â

Â

Â

MST2 Tiffany Wright recovers the sediment trap and carefully hands the samples to the scientist.

MST2 Tiffany Wright recovers the sediment trap and carefully hands the samples to the scientist.

The science conducted on the ship is dependent on the successful deployment of the marine sampling equipment from the multi-core to the sediment trap to the plankton nets to the CTD. While the operation and positioning of the boat at a sampling location is conducted up on the Bridge, the Marine Science Technicians (MSTs) play a vital role in the work conducted by the scientists on deck. They help to deploy and recover all of the sample collecting instruments and enable the scientists to complete their experiments. They are an invaluable resource to the science party.Â

The job of an MST in the Coast Guard is usually a land-based job, but two ships have MSTs, both of which operate in the Arctic. The Healy is unique in that her mission is to contribute to the advancement of science and our understanding of Arctic and Sub-Arctic oceanography. When I spoke with MST1 Rich Layman and MST1 Eric Rocklage about the being an MST aboard the Healy, they had nothing but positive things to say and told me how much they enjoyed the direct contact and involvement with the science being conducted on board. Working with the science party and out on deck with the sampling instruments provided a unique opportunity in the Coast Guard and the science party values their hard work and dedication tremendously. The MSTs are truly an important element in getting the science accomplished aboard the Healy. Â

LTJG Stephen Elliot and MST1 Chuck Bartlett assist scientists deploy the multi-core, a sea floor sampling device.

Â

MST1 Rich Layman straightens the winch cable before deploying the MOCHNESS, a multiple net sampling device designed to collect plankton samples at various depths.

Â

MST1 Eric Rocklage prepares the CTD to be deployed. He must make sure that the ice does not interfere with the cable.Â

Â

Â

MST3 Tom Kruger retrieves a Van Veen Grab which is sent to the bottom to collect mud and the critters living on the sea floor.Â

Â

A Glaucous Gull, one of the more common species in the Bering Sea, follows the ship as we steam to the next station.

In my opinion, the luckiest researchers on the ship are the ornithologists, Kathy Kuletz and Liz Labunski from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, who stay on the bridge from sunrise to sunset conducting bird surveys. They don’t miss a bird, seal, walrus or beautiful vista as they identify and log all of the birds and mammals we encounter along the ship track. The objective of their research is to contribute to the North Pacific Pelagic Seabird Database which has data starting in the 1950s! By cataloguing what is in the Bering Sea at various times of year and under various ice conditions, they add valuable data to this tremendous resource for all researchers to use. They have more than twenty cruises planned for this year and more in future years! In addition to adding to the database, Kathy and Liz, as part of their BSIERP (Bering Sea Integrated Ecosystem Program) study, will correlate bird densities with the oceanographic and fisheries data collected on this cruise and the others they will sail on.Â

Liz has been aboard the USCGC Healy since the beginning of March and has observed that there has been low diversity of the bird species; perhaps because of the heavy ice the Bering Sea is experiencing this year. The dominant species have been the Common Mure, Glaucous Gull, and Black-Legged Kittiwake. In addition to these species, they have observed Black Guillemots, Slaty Backed Gulls, Ivory Gulls and a variety of other species. It never ceases to amaze me that no matter how far from shore I can be and in seemingly freezing icy condition, the ship always encounters birds. Kathy and Liz use a specialized computer program which correlates the exact GPS location with their observations so that their distribution data is very accurate.  With this data and the oceanographic data collected on the cruise, they hope to gain an understanding of how large scale changes to the Bering Sea ecosystem may affect the populations and distribution of sea birds.Â

Liz Labunski, always with binoculars in hand, spots a pair of ivory gulls flying around the ship. These birds are not commonly found in our survey area but farther north. They blend in perfectly with the sea ice making them hard to follow. Â

A small flock of Black-Legged Kittiwakes rests on a small chunk of ice along the ice edge.

Â

Â

Â

Today was our last day in the ice as we approached the ice edge. The ice was broken up and seemed slushy with more substantial patches mixed in. On those patches, seals, sea lions and birds rested. The marine life in these waters is incredible. We have been looking for whales and albatross here in the open water but have yet to see them. Perhaps we will encounter them on our steam to Dutch Harbor beginning tomorrow afternoon.Â

The research on the cruise is winding down and most of the scientists are packing up their gear with the exception of the hydro team which is collecting water samples every ten miles along the 70m isobath on our way back to Dutch. It is exciting to be back in open water and we are hoping for good weather for the remainder of the cruise. Â

A herd of walrus lounge on an ice floe. Â

This Bearded Seal was sleeping on the ice as we passed on the ship. He is molting so his color pattern was mottled and very interesting.

Â

Seal Pups on the ice. The mother will head into the water as the ship passes and the pup will remain on the ice where their coat keeps them relatively camouflaged.

By far one of the most beautiful animals I have ever seen, a Ribbon Seal rests on the ice during a snow shower.

A Stellar Sea Lion was resting on a small piece of ice in mostly open water. Â

Â

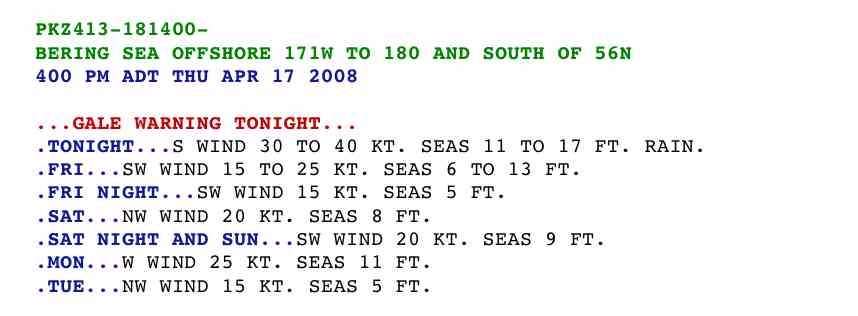

It is very early Monday morning here on the Healy and we are finishing up our survey of the 70m isobath and packing up to head to port. Yesterday was filled with finishing up experiments, packing, and getting ready to hit open water. A low pressure system that we have been watching to the south is heading north towards us so that could mean big seas for our transit to Dutch Harbor. Because of the impending weather, much of the packing that would be done today had to be completed yesterday in order for everything to be secured for high seas. I am in the process of packing up all of my cameras, chargers and other gear so that nothing gets damaged if the ship gets tossed about. The Healy is a very smooth riding ship and we are only expecting 15-20 foot swells so it should not be too dramatic. (I hope.)Â

In the meantime, we are doing CTD casts every ten miles to complete our survey of the area. A CTD is a conductivity temperature depth recorder and is the primary tool used by oceanographers to determine the physical parameters of sea water. Sensors on the instrument measure temperature, salinity, and depth while bottles on the rosette structure collect water samples at various depths. This water can then be tested for dissolved oxygen, organic and inorganic carbon, and other nutrients. The CTD gives us information about the physical properties of the water column so that the biology (the animals) can be put into a context of their environment. An invaluable tool, nearly all of the scientists on board sample the water from the CTD and/or use the physical data obtained by the hydro team. (# of CTD casts done). One has been conducted at every station and along specific survey lines.Â

We are scheduled to be finished with science and sampling sometime this evening when we will begin our transit to Dutch Harbor. Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

The CTD, Conductivity Temperature Depth Recorder, comes up from 70m where it collected water samples every 15m on its way back to the surface.

Â

Â

Â

John Casey from the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences filters water from a CTD cast. He is looking at carbon ratios in the waterÂ

John Casey from the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences filters water from a CTD cast. He is looking at carbon ratios in the waterÂ

Â

Â

Â

I woke up to calm seas and a stunning morning despite the weather forecast. We are cruising at 15 knots between stations and have almost completed our entire survey which included over 200 sampling stations. There have been passing whales, birds and occasional ice floes with seals and sea lions resting in the open sea. It feels like the Bering Sea is smiling upon us as we cruise towards Dutch. I am nearly finished packing and am hoping for a beautiful sunset for our final night at sea.Â

Â

A few hours later, our beautiful calm day turned into a rough Bering Sea evening. We are in some of the biggest seas that we have seen since starting our voyage and it seems that it is building. We had no wind this morning with 1-2 foot seas. Within an hour, the seas have built and the wind is blowing at 22 knots. The Bering Sea has shown up to say hello before we disembark.  Â

Â

Â

Our trip to Dutch Harbor was all but comfortable. We had 45 knot winds with 8-10 foot swells. Because of our course and the necessity of arriving in Dutch at 0900, the ride was particularly uncomfortable as we were in the trough most of the night. Sleep was not really a possibility plus I was anxious not to miss pulling into Dutch Harbor as I heard it was quite beautiful.

I woke up to fog and rain so it would not be clear for our entrance into Dutch. Regardless I wanted to be up on the bridge for the docking. Entering the harbor was beautiful with snow-capped mountains jutting out of the sea. The fog hung low on the mountains with rain falling as the pilot boat came to greet the ship for assistance in the docking. An hour or so later, we were moored to the dock and the brow was going down. We had arrived in port and could get back on dry land. It was time to leave the ship that had become our home for the past few weeks and begin exploring Dutch Harbor and Unalaska.Â

Â

The USCG Cutter Icebreaker Healy moored in Dutch Harbor.Â

Once checked out of the ship, I headed to the airport to rent a truck to explore the area. I rented a F-250 pick-up that was held together with ratchet straps and some duct tape. As I was leaving the rental agency, one of the men working there, told me to make sure to put it in four wheel drive if I got to any questionable spots in the road. This certainly was going to be an adventure.Â

I was off on my adventure exploring Dutch Harbor with two other members of the science party who wanted to join. I drove down every road until it was impassable stopping along the way to enjoy the views of the water. There are a few things that stand out in my mind about Dutch Harbor: crab pots, fishing boats, bald eagles, and potholes. The roads are rough and nearly all are lined with crab pots; often there are eagles perched on top of the crab pots; and the roads were filled with potholes that I seemed not to be able to miss.Â

Â

Â

The sun ducked in and out for the rest of the afternoon. We went along the water and stopped to check out some tide pools where four otters were frolicking nearby. The tide pools were filled with chitons, mussels, barnacles, snails and different species of seaweed. We enjoyed the vistas from this spot and then piled into the truck to continue down the road where we encountered the rental car guy changing someone’s tire. That made me a little nervous but I figured I would just be a bit more careful of the potholes. We came to a black sand beach with little waves gently rolling in and an outflow of water feeding into the bay. I continued along until the road got narrow and windy and then I hit a snow embankment. I had to back down this road with a sheer cliff on one side and a hillside with a drainage trench on the other. Needless to say we made it and it was worth it because the view from the top was stunning.

Â

Â

There was a single lane road to the right which we decided to head up to see what was there. About a mile up the road, we found horses! They were grazing in a meadow with the rain falling and the wind building.Â

Then we headed back towards the town of Unalaska. There is not much in Unalaska. The one infamous bar in town was recently shut down leaving only two bars, one at the hotel and one at the airport. This is big news in a fishing town. I drove up to the top of one of the hills to get an overview of the town. The setting is beautiful and it must be spectacular in the summer. It is mud season now so everything is on the grey/brown side. There is a Greek Orthodox Church in Unalaska much like the one in St Paul.Â

Â

Â

After a long day of exploring, we headed back to the hotel to wind down from the day and reflect on a great expedition. Flying out of Dutch Harbor is supposed to be an experience so I have that to look forward to tomorrow afternoon. Â

Â

Â

It is always bittersweet when an expedition comes to an end. From start to finish, this expedition was filled with the excitement of the unknown and the magical, from flying into the fog of St. Paul to frolicking on the Bering Sea ice. I am very excited about all of the work I accomplished and look forward to editing and putting everything together to share, but at the same time, I was not ready to come back to the bustling city. Â

A tremendous amount of amazing cutting edge science was accomplished and I look forward to seeing how all of the scientists collaborate to make the project come alive and gain a more complete understanding of the Bering Sea ecosystem.Â

I want to thank all of the scientists who allowed me to follow and learn about their work, and the crew of the USCGC Healy. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Carin Ashjian, the chief scientist of the expedition, and Captain Lindstrom. It was a fantastic expedition and I look forward to many more in the future.Â

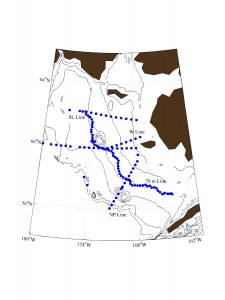

This is a map of where samples will be taken during the cruise.

This is a map of where samples will be taken during the cruise.

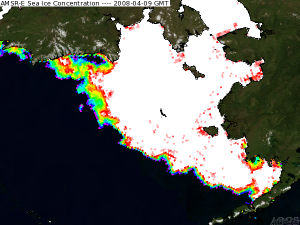

Some of my gear.

Some of my gear. Â The white indicates where there is ice coverage. Â This is a satellite image much like a sea surface temperature map or productivity map.Â

The white indicates where there is ice coverage.  This is a satellite image much like a sea surface temperature map or productivity map.

The Crab Processing Plant

The Crab Processing Plant

New Tow in the Snow

New Tow in the Snow Krill

Krill The Multicore

The Multicore

Retrieving the Sediment Trap

Retrieving the Sediment Trap

The multi-core can take up to eight samples each deployment.

The multi-core can take up to eight samples each deployment. Dave Shull examines a core.

Dave Shull examines a core.

The krill sampling team and the marine science technicians bring in the bongo nets in the darkness.

The krill sampling team and the marine science technicians bring in the bongo nets in the darkness. A bucket teeming with copepods, krill and other plankton. Without a microscope, it looks like thick red/orange soup.

A bucket teeming with copepods, krill and other plankton. Without a microscope, it looks like thick red/orange soup.

Deploying the ring net used to collect the copepods and krill needed for the team’s experiments.

Deploying the ring net used to collect the copepods and krill needed for the team’s experiments. Phil Alatalo sorts through the sample for animals to use in the experiments.

Phil Alatalo sorts through the sample for animals to use in the experiments. Copepods

Copepods Krill

Krill On the bow, the incubators hold the samples for 24 hours in ambient sea water with constant agitation

On the bow, the incubators hold the samples for 24 hours in ambient sea water with constant agitation Dr. Campbell carefully picks female copepods out of a sample to put into the bug hotel for their egg studies

Dr. Campbell carefully picks female copepods out of a sample to put into the bug hotel for their egg studies Dr. Campbell puts a tray of female copepods into the bug hotel for the egg growth experiment.

Dr. Campbell puts a tray of female copepods into the bug hotel for the egg growth experiment.

Dr. Ashjian and Dr. Campbell remove the animals from the experiment jars in order to preserve them for analysis of carbon in the lab.

Dr. Ashjian and Dr. Campbell remove the animals from the experiment jars in order to preserve them for analysis of carbon in the lab.

The sediment trap buoys adrift in the Bering Sea

The sediment trap buoys adrift in the Bering Sea

The instrument is about to come aboard as the small boat grabs a tender line from the ship.

The instrument is about to come aboard as the small boat grabs a tender line from the ship.

The tubes with the samples are carefully collected by Jonathan Whitfield and MST Tiffany Wright for analysis.

The tubes with the samples are carefully collected by Jonathan Whitfield and MST Tiffany Wright for analysis. The surface collection tubes sometimes capture animals from the water column.

The surface collection tubes sometimes capture animals from the water column. MST2 Tiffany Wright recovers the sediment trap and carefully hands the samples to the scientist.

MST2 Tiffany Wright recovers the sediment trap and carefully hands the samples to the scientist.